Harper's Bazaar Arabia - Studio Visit

A Visit To German-Iranian Artist Timo Nasseri’s Studio

The Berlin-based artist is set for his first UAE exhibition that will open at the Maraya Art Centre in Sharjah this month

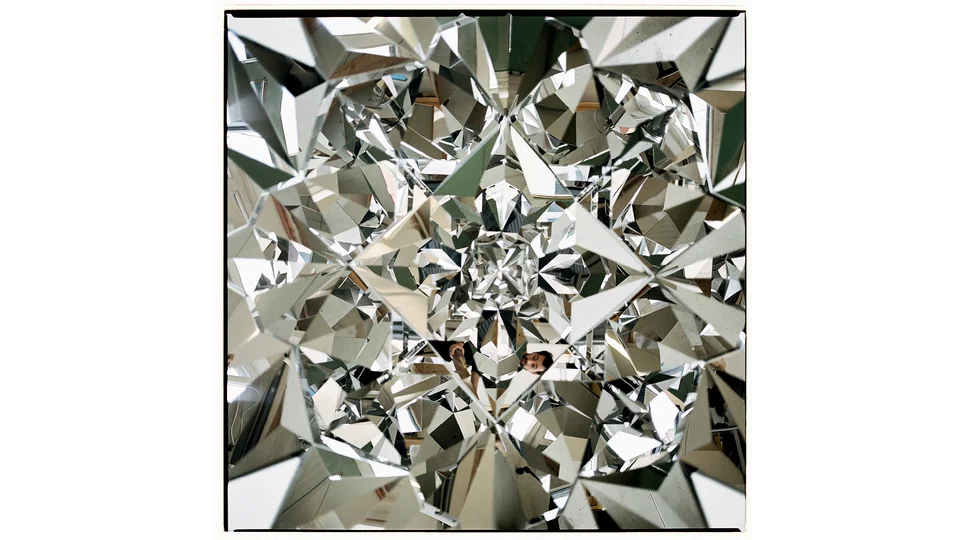

Detail 1

Walking into artist Timo Nasseri’s studio, something shiny catches my eye. Standing in the far corner of the room, slightly concealed behind crates, I recognise it immediately. It is one of Nasseri’s Muqarnas—large configurations made out of polished stainless steel that resemble the honeycomb vaults so prominent in Islamic architecture.

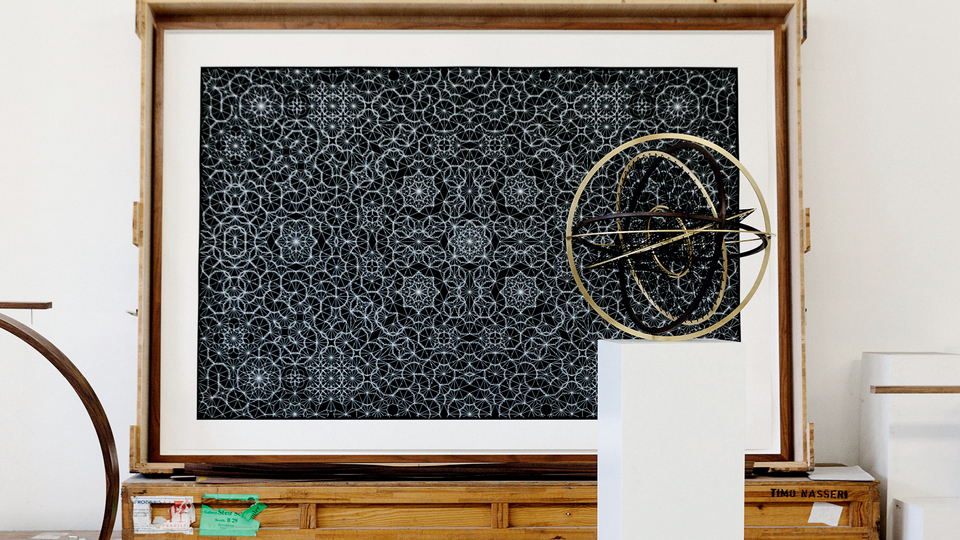

Detail 2

The studio is generously sized, but there is barely any empty space. Stacked wooden crates occupy the length of the room, a monumental ink drawing hangs behind a workbench, and at the far end, sharing a wall with the Muqarna, I make out an assembly of sculptures and a painting. The building, a converted warehouse, is located in a south-eastern suburb of Berlin, a former industrial hub that fell into ruin after German Reunification and has recently become popular with artists and creatives.

New residents include artist Olafur Eliasson, who recently announced plans to open his second Berlin studio in a former manufacturing plant, and rock star Bryan Adams, who is converting a large factory building into a photography workshop. Nasseri’s studio is slightly on the periphery of this sudden cultural makeover—his immediate neighbours are a carpenter, who occupies the adjacent building and the owner of the property, who lives in the unassuming house opposite.

I follow the artist through the ground floor and up the stairs to the mezzanine level, where we take a seat at a small table by the window. The room looks comfortable and lived-in: a large desk and bookshelves line the walls; the small but well-stocked kitchenette gives me the impression that Nasseri spends a lot of time here. The occasional sound of an electric saw and muted voices reach us from the floor below. It is a busy time for the German-Iranian artist. He's just back from installing his solo show at Ab/Anbar Gallery in Tehran and in December, his first exhibition in the UAE will open at the Maraya Art Centre in Sharjah. Also in December, a major new installation by the artist will go on display as part of the NGV Triennial in Melbourne.

Despite his busy schedule, Nasseri is generous with his time. He explains at length how the illustrations of Muqarnas in his father’s library left a deep impression on him as a child, and how, years later, as a young adult travelling along the Silk Road, he became fascinated with the honeycomb vaults he encountered time and again in mosques. “I became completely captivated by them. I couldn’t understand how they were built,” he says, “what geometrical order they followed.” At some point he realised that the only way to fully comprehend their magic was to build his own.

He pulls out a small pencil drawing of an intricate geometrical pattern with minuscule, annotated measurements—his first sketch for a Muqarna. While the original structures embellish the domes of mosques, for Nasseri it was important to lower them to eye-level, hollowing out the wall to create a cavity the depth of which, standing in front, you can’t really fathom. “I wanted to remove the religious aspect, I wanted to bring it down from the ceiling. I see things in a very Western way, so perspective, and the relationship to the viewer, always play a major role.”

The fact that the sculptures are made out of reflective stainless steel, however, is a clear reference to Islamic crafts. The use of mirror fragments in Arabic decorative art dates back to the 15th century, when the mirror plates would often break in the long transport routes from Venice, where they were manufactured, to the Orient. The shards were considered too precious to throw away, so they were used as inlays in decorative objects. This synthesis of Western and Islamic influences is something that runs through Nasseri’s art.

He shows me a large ink drawing that leans against the wall. Drawn using white ink on black paper, it forms a mesmerising geometrical pattern that from a distance resembles a map of the stars; bright points of light appear where the lines converge. Known as the One And One series, these drawings follow the same geometrical order as the Muqarnas; starting from a central point they can grow infinitely in an infinite number of combinations. Each drawing takes several weeks to complete and is painstakingly hand-drawn using a compass and ruler. “It’s like a form of meditation making them,” he laughs. “But you have to concentrate. If you mess up you have to start all over again.”

Despite having lived his entire life in Berlin, the artist acknowledges the profound influence his father, an Iranian surgeon who immigrated to Germany in the 1950s, had in his life. “I have a different sensibility. I grew up with different images and different aesthetics. My father’s house was totally Iranian; he had it all: the furniture, the carpets, the Persian miniatures… And he was a great storyteller,” he says. “He would mix traditional oriental tales with his own stories.”

Although he didn’t grow up speaking Farsi, it was this position of being “in-between” two cultures that triggered his fascination for Islamic calligraphy. This is the focus of his latest work, The Unknown Letters, an ensemble of wooden sculptures that will go on display for the first time in their entirety at the Maraya Art Centre. Drawing inspiration from the life and work of the 10th-century master calligrapher Ibn Muqla, whose attempts to reform the Arabic alphabet were condemned as blasphemous and severely punished, Nasseri has created a group of four new imaginary letters that derive their forms from star constellations.

Before leaving the studio, he shows me the sculptures: sinuous shapes carved from walnut wood, sanded down for hours and polished with wax. Carefully laid out in crates, they look as if waiting patiently: ready to embark on their journey to the Orient.